Courrier des statistiques N4 - 2020

INES, the Model that Simulates the Impact of Tax and Benefit Policies

The INES model, co-produced by INSEE and DREES and more recently the National Family Allowance Fund, simulates the main taxes and benefits in France. Based on a sample of individuals and households from the Tax and Social Incomes Survey, the microsimulation model uses a data set rich in information on people’s socio-demographic characteristics, housing, employment and income. This article tells the story of INES, describes the data used, the tax and benefit transfers simulated and how the model functions, as well as its main characteristics.

The studies carried out using this microsimulation model help to shed light on the public debate in the fields of monetary redistribution, taxation or social security protection. The first three applications described are annual studies, which provide an ex-post analysis of the effects of the tax and benefit system and its evolutions: analysis of redistribution, assessment of the reforms implemented each year and nowcasting of poverty and inequality indicators. The following two concern ex-ante analyses: simulations of fictitious tax and benefit reforms and regular political orders on reform projects. Two examples of original and more selective studies conclude this overview.

- A Model to Simulate Tax and Benefit Legislation

- Box 1. INES, already a long story

- The Model’s Input Data

- Box 2. The Data used by the INES Model

- The Tax and Benefit Measures Simulated by the INES Model

- How the Model Works Today

- A Static Model, but one that can Introduce Behavioural Effects

- Detailed Documentation and an Open Source Model

- Recurring Uses of the INES Model

- Box 3. Two Examples of Original Studies based on INES

- Are the Sources Used by INES to be Expanded?

The analysis of the impact of tax and benefit transfers is an important field in the evaluation of public policies. While many studies assess the effect of a particular transfer, it is difficult to obtain an overall view of the tax and benefits system and its impact on standards of living. In fact, the legislation on taxes and benefits in France is complex (based on numerous legal codes: the General Tax Code, the Social Action and Family Code or the Social Security Code) and there are many interactions between tax and benefit transfers. Microsimulation models make it possible to identify the effects of these different measures on the incomes of individuals and their families, taking into account their specific characteristics. These models provide an overall analysis of transfers according to family configuration, household living standards or the employment status of individuals. They also make it possible to take into account all the interactions that exist between the measures. Microsimulation models have thus acquired “a central, though slightly misunderstood, position in the field of analysis of tax and benefit policies” (Legendre, 2019).

This article provides a presentation of the INES microsimulation model. Part of the family of static microsimulation models, INES simulates the main taxes and benefits in France. It makes it possible to carry out in-depth studies to shed light on areas of debate in the fields of monetary redistribution, taxation or social security protection.

A Model to Simulate Tax and Benefit Legislation

“Static” microsimulation models simulate, for each individual, the taxes they pay and the benefits they receive based on the legislation’s schedules, allowing their disposable income to be determined. To do so, they rely on real data (age, family composition, income, employment status of individuals, etc.). It is possible to vary the schedules and study the effect of those variations on household disposable income or on public finances, and thus to shed useful light on the effects of these public policies.

These models thus make it possible to assess the effect of a variation of the schedules for certain social security taxes or benefits on the living standards of the people concerned, to identify the winners and losers of the reforms, or even to measure the effect of the reforms on the poverty rate, living standards inequality and public finances. To do so, two situations are compared: one in which the schedules have been modified, compared to a “counter-factual” one, generally with the legislation currently in force.

This was the goal behind the creation of the INES model in 1995. Having initially been developed by INSEE (David et alii, 1999), DREES came on board in the early 2000s and CNAF joined in 2016 (Box 1). From the beginning of its story, the INES model has been used as a decision support tool to calibrate major tax and redistribution reforms. The model has thus been used to calculate figures for the introduction of the prime pour l’emploi (an earned-income tax credit) in 2001, the creation and implementation of the revenu de solidarité active (RSA – a statutory minimum income coupled with an in-work benefit) in 2009, the prestation d’accueil du jeune enfant in 2014 (PAJE – an early childhood benefit) and the prime d’activité (an in-work benefit) in 2016. In 2019, it was used to calibrate the response measures to the social emergency following the gilets jaunes (yellow vest) movement and to fuel work on the revenu universel d’activité (RUA – a merger of means-tested benefits).

Box 1. INES, already a long story

The INES model was created in 1995, in the Social Studies Division of INSEE, following the recommendations of the Guibert report(i). Two other models had been developed in France, but each with its own shortcomings(ii):

- the modèle d’impôt sur le revenu (income tax model – MIR) only simulates income tax;

- the database of the SYSIFF model is based on the Family Budget survey and is not robust, as income is reported on the basis of declarations.

Since its conception, INES has compensated for these shortcomings by simulating the main taxes and benefits based on the enquête Revenus fiscaux (Tax Income survey – ERF) since 1990: this source combines fiscal data and socio-demographic information from the census. The model was presented as early as 1996(iii) and documented in 1999 (David et alii, 1999). It quickly became used in the political debate to assess family policy and to evaluate the proposed means-testing of family benefits, the results of which were published (Thélot and Villac, 1998)(iv).

In the early 2000s, DREES (the Research, Studies, Evaluation and Statistics Directorate of the French Ministry of Health and Solidarity) joined INSEE to develop the INES model(v). The new version is based on the 1996 ERF, which pairs the Labour Force survey and the tax declarations; it was presented in 2003 (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAlbouy et alii, 2003). The collaboration makes it possible to share the costs of developing and maintaining the model, which is consequently “more reliable than the previous one due to cross-validation procedures and exchanges of knowledge between the two teams” (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBessis and Cotton, 2019).

In 2006, the ERF was replaced by the enquête Revenus fiscaux et sociaux (Tax and Social Incomes Survey – ERFS), based on the Labour Force Survey and tax and benefit data.

A new important stage took place in 2016 with the model’s source code being made available publicly on the ADULLACT (Association des développeurs et utilisateurs de logiciels libres pour les administrations et les collectivités territoriales) website, and the National Family Allowance Fund (Caisse nationale des allocations familiales – CNAF) joining the INSEE-DREES teams to co-manage the model.A new important stage took place in 2016 with the model’s source code being made available publicly on the ADULLACT (Association des développeurs et utilisateurs de logiciels libres pour les administrations et les collectivités territoriales) website, and the National Family Allowance Fund (Caisse nationale des allocations familiales – CNAF) joining the INSEE-DREES teams to co-manage the model.

(i) This report was commissioned in 1994 by Michel Glaude, Director of the Demographic and Social Statistics Directorate of INSEE at the time and also the author of the first microsimulation experiments at INSEE.

(ii) See the article by Didier Blanchet in this same issue, as well as (Legendre, 2019) and (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBessis et Cotton, 2019).

(iii) During a study day held at INSEE, which resulted in the first review file in France dedicated to microsimulation methods (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletINSEE, 1998).

(iv) This report, ordered by the Prime Minister, contains the first published results from INES and an initial summary presentation of the model. The consequences of the report will be the cancellation of the introduction of means-testing of family benefits and the capping of the benefit due to the family quotient.

(v) At that time, the meaning of the acronym becomes “INSEE-DREES”, whereas it was previously a contraction of “Insee-études sociales” [INSEE Social studies].

The Model’s Input Data

Unlike the models of the case studies for representative agents, which simulate legislation for a fictitious individual, the microsimulation models are based on the observation of real situations and are, therefore, closely linked to the data used. Since 2006, the INES model has mainly used data from the Tax and Social Incomes Survey (ERFS) (Box 2). This source contains hundreds of detailed information entries on income, employment or family status for a sample of more than 50,000 households and 130,000 individuals. The ERFS is INSEE’s preferred source for the analysis of living standards. This richness of information makes it possible to finely simulate the social security benefits, taxes and contributions that depend on many variables, which are not always present in fiscal sources alone: family profile, labour market history, number of hours worked, type of job and business, rents, place of residence, disability status, etc.

The sample from the ERFS is representative of the French population living in ordinary housing and in metropolitan France (Box 2). This makes it possible to produce analyses by dividing the population into ten groups of equal size according to their living standards (from the poorest 10% to the wealthiest 10%), or according to employment status or family configuration. Some results can be given at finer levels, by dividing the population into 20 groups, for example, in order to estimate the effect of certain specific measures that mainly affect the wealthiest, such as the replacement of the impôt de solidarité sur la fortune (ISF – solidarity tax on wealth) with the impôt sur la fortune immobilière (IFI – real estate wealth tax) (Paquier et alii, 2019). However, the estimated effect at the extremes is less robust than those estimated for each tenth and the sample size does not allow for more detail, such as per hundredth for example, unlike exhaustive sources.

Finally, it should be noted that data on income for year N are only available in year N+2: for the purposes of the model (simulation of legislation for the year N+2), this requires “ageing” the ERFS data (see below).

Box 2. The Data used by the INES Model

- The Tax and Social Incomes Survey (ERFS)

For each year N, the ERFS is composed by performing matching between the respondents to the Labour Force Survey for the 4th quarter and the fiscal sources for the year, i.e. the income declarations for year N (completed in March N+1), housing tax as at 1 January of year N and the files from the caisse nationale des allocations familiales (National Family Allowance Fund – CNAF), the caisse nationale de l’assurance vieillesse (National Old-Age Pension Fund – CNAV) and the caisse centrale de la mutualité sociale agricole (Central Agricultural Social Mutual Fund – CCMSA) which provide the social benefits paid. Note that the model does not use the ERFS data on benefits or income tax directly, rather it simulates them*.

The latest version of the model (2018) uses the 2016 version of the survey. The sample on which the ERFS 2016 is based, drawn from the housing tax files, is composed of 120,000 individuals for 54,000 respondent households, so-called “ordinary” households in Metropolitan France: people living in collective housing (homes, prisons, hospitals, etc.), those living in mobile homes (mariners, etc.) and homeless people are thus excluded.

- The Other Databases used by the Model

The INSEE Family Budget survey is used to impute the consumption data based on which the VAT paid by households is simulated in INES. This survey has been carried out since 1979 on household consumption, with the objective being to measure not only the expenditure, but also the resources of households living in France (Metropolitan France and French overseas departments and territories) as accurately as possible. It covers all so-called “ordinary” households.

The Housing survey is used in INES to impute rents, which are absent from the ERFS. The aim of the survey is to describe the housing conditions of households and their housing expenditure and therefore it contains rents and charges for tenants, together with a lot of other information.

In order to simulate the French wealth tax (impôt sur la fortune -ISF-, and the impôt sur la fortune immobilière -IFI), it is necessary to have information on the wealth of individuals. To that end, we use matching based on the INSEE Household Wealth surveys. These surveys describe real-estate, financial and professional assets of households and their debt, based on a sample drawn from housing tax files or other fiscal sources. In order to better understand high wealth levels, we also use files specific to the ISF and the IFI, recently made available by the Directorate-General of Public Finance (DGFiP) (Paquier et alii, 2019).

* However, the ERFS data on certain benefits are used in the model, such as the Allocation adulte handicapé (AAH) to identify persons with disabilities for example.

The Tax and Benefit Measures Simulated by the INES Model

For each person, home or household, depending on the level of analysis required, the INES model uses the ERFS data and applies all the rules of the legislation to them.

It is thus possible, for example, to identify the households eligible for the prime d’activité (in work benefit), using the family composition (number of dependent children, whether the parents are together or it is a single-parent family) and people’s monthly employment situation reconstituted based on an “employment calendar” and the household income from ERFS database. By using all this information for each potential household, the model makes it possible to simulate an entitlement to the benefit which is then integrated into that household’s disposable income, by taking into account the possibility of non take-up of the benefit, i.e. that people do not claim the benefit even though they are entitled to it.

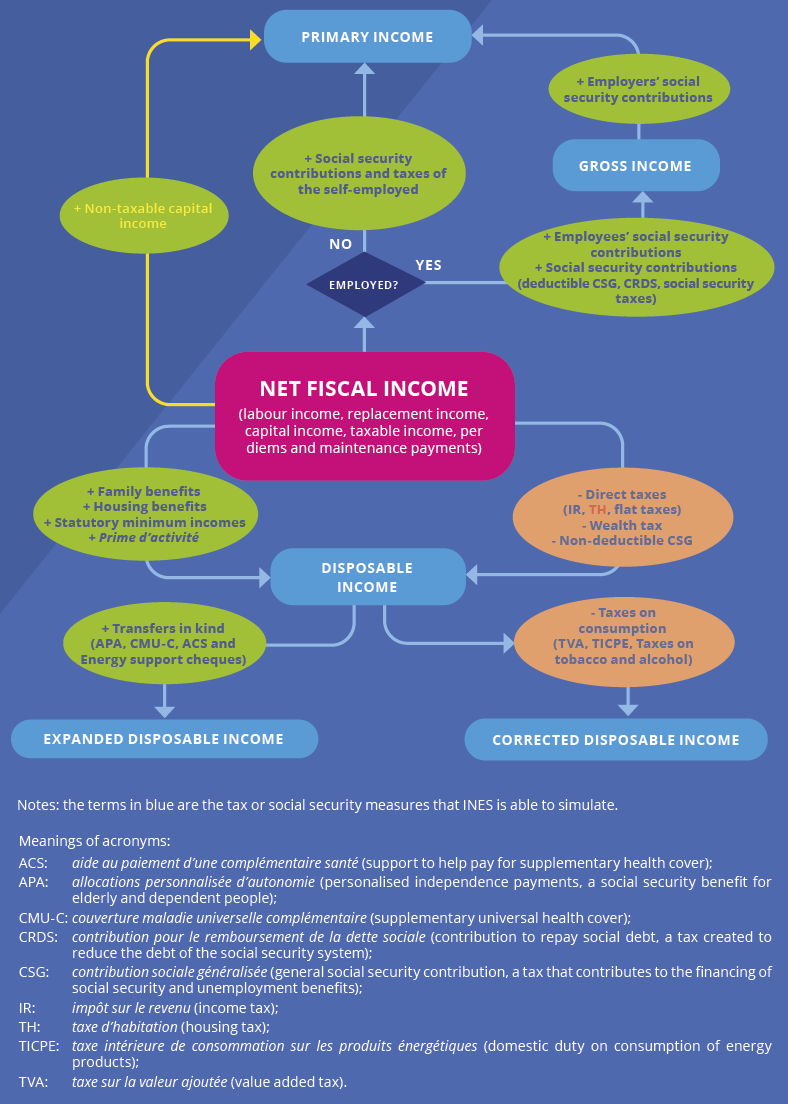

Income is crucial for simulating the various transfers. The incomes used as input data for the model, and which remain constant in the event of a change to the amount of the various transfers received or paid, are the posted net incomes in the tax return (this is referred to as the fixed point of the model). Based on these posted incomes, the INES model simulates most tax and benefit transfers, as illustrated in Figure 1. The social security contributions and taxes are simulated, whether they are payable by the employer, the employee or the self-employed person. Similarly, all other taxes and subsidies based on the total payroll are simulated, such as the crédit d’impôt compétitivité-emploi (CICE – tax credit for employment and competitiveness) or the tax on employees or transport. For direct taxation, the model simulates income tax, all tax credits and flat taxes3. Recently, the development of a module on household wealth (Paquier et alii, 2019) has made it possible to simulate tax on wealth (impôt de solidarité sur la fortune). Finally, the indirect taxation module (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAndré et alii, 2016) makes it possible to add indirect taxes such as value added tax (VAT), the taxe intérieure de consommation sur les produits énergétiques (TICPE – domestic tax on consumption of energy products) or the taxes on tobacco products.

With respect to the benefits paid to households, the model makes it possible to simulate means-tested and non-means-tested family benefits, personal housing benefits, statutory minimum incomes, the prime d’activité and the garantie jeune (a benefit for NEETs aged 16 to 25). For some of these benefits, such as the prime d’activité, non take-up is taken into account. Finally, certain in-kind transfers can also be simulated, to allow an analysis of “expanded” disposable income (Figure 1).

Most often, these transfers are simulated based on the legislation of the previous year, but they may also be simulated based on other legislation (see below).

Figure 1. The Different Concepts of Income and the Tax and Benefit Measures Simulated Using INES

How the Model Works Today

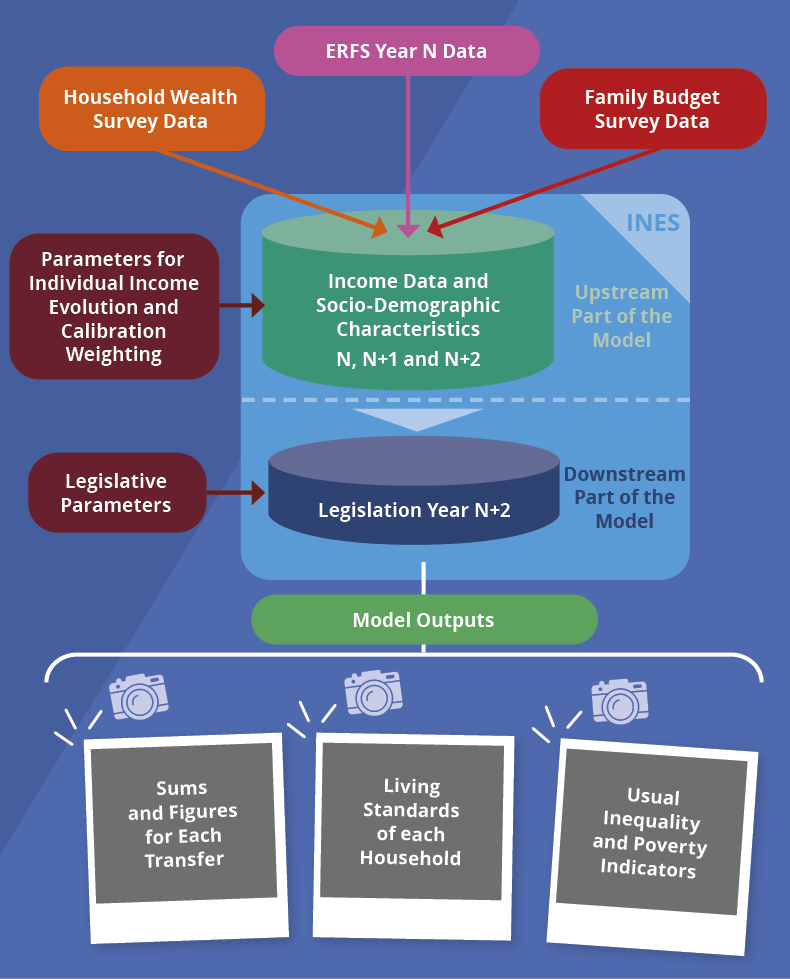

The INES model simulates these tax and benefit transfers thanks to a sequence of more than 100 computer programs. To do so, it uses as its input a version of the ERFS which is first reworked in the “upstream” part of the model, then used in the “downstream” part to simulate the various transfers of the tax and benefit system for a given legislation year, based on the legislative schedules. The “upstream” part makes it possible to ensure that the format of the data will be usable by the rest of the model. The “downstream” part contains all of the programs that simulate the legislation. In this part, the parameters of the legislation (and potential non take-up) are applied to the data output of the upstream part. This is the operation to which we are referring when we use the term “simulation”. It differs from the “imputation” present in the upstream part, which are intended to add to or rely on external data.

As an output, the model makes it possible to determine the number of recipients or persons subject to the various transfers and the financial sum distributed, the disposable income and the living standards of households, as well as the various usual inequality and poverty indicators (Figure 2). The fact that the transfers are simulated makes it possible to compare all the results of the model in different situations, in accordance with legislative changes, and to analyse the redistributive effects.

In order to function, the model needs two important parameters: the reference year (the year of the input ERFS) and the legislation year to be simulated. As it is currently used, this pair is generally composed of the latest version of the ERFS available (year N) and the year of legislation corresponding to two years later (year N+2).

Regardless of the legislation year selected, the ERFS data are “aged” by two years in the upstream part of the model, so as to best represent the population for years N+1 and N+2. To that end, the model takes into account a multitude of socio-demographic (age pyramid, socio-professional categories, etc.) or economic (inflations, salary evolution, etc.) developments between the reference year and two years later.

Specifically, this ageing process is carried out in two stages, one calibration weighting stage in which the weightings of each household in the ERFS are changed and one individual income evolution stage:

- we first make sure, for example, that we obtain the same number of children, unemployed people and couples as in the INSEE sources for year N+2, then we change the income between year N and year N+2. For example, if the number of unemployed people increased between year N and year N+2, the weighting for unemployed people is increased in the sample in the first stage;

- for the second stage, a different evolution is applied according to the type of income (salaries, retirement pensions, unemployment benefits, financial income, agricultural income, etc.) and according to the year. Between year N and year N+1, newly available tax data are generally used, and between year N+1 and year N+2 INSEE data from national accounts, the French Central Bank (for financial income), or from official statistical surveys are used.

Figure 2. Data and Parameters, the Inputs of the INES Model

The model is updated each year between February and October to simulate the previous year’s legislation (Figure 3). In 2020, the model thus evolves to incorporate the 2019 legislation. This update consists, on the one hand, of updating all the parameters of the various legislative schedules. For example, in 2020, the flat amount of the allocation adulte handicapé is updated, which rose from €860 to €900 in November 2019. It also involves coding work on the new tax and benefit measures, which can be significant when major reforms are introduced.

In addition to these annual updates, the model is continuously amended to be improved or corrected. In addition, supplementary modules are created on a regular basis. These supplementary models are optional in the execution of the model and make it possible to extend the scope of the measures covered and to flesh out the outputs with, in particular, an analysis of indirect taxes (mainly VAT and excise duties on tobacco and alcohol) and taxes on wealth.

Figure 3. Calendar for the ERFS and Updating INES

A Static Model, but one that can Introduce Behavioural Effects

As it is most commonly used, the model does not take into account any behavioural effects in the evaluation of tax and benefit reforms, it is purely static.

However, behavioural responses may result from the reforms implemented on simulated transfers: for example, a fall in tobacco consumption following the tax rise, an increase in dividends paid following the introduction of the prélèvement forfaitaire unique (flat tax on capital income – PFU) in 2018 or even the change in the labour supply following the reforms to the prime d’activité.

The effects of macroeconomic closures are also not addressed, such as the positive impact of higher incomes on consumption and GDP and, in turn, on employment and incomes. Introducing these impacts requires making many assumptions, relying on work that is often divergent and questionable, however serious it may be. Static analysis is less contestable and thus the choice to not take behavioural effects into account is “virtually systematic by most governments and independent institutions responsible for costing economic measures” (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBach et alii, 2020).

Thus, it must be borne in mind that the effects measured are generally short-term effects, not taking into account dynamic effects. However, some studies have estimated behavioural elasticities based on the INES model (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletFugazza et alii, 2003; Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLehmann et alii, 2013; Sicsic, 2019). The evaluation of the introduction of the prime pour l’emploi (earned income tax credit) in 2001 was thus carried out taking into account the effects on the labour supply (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletFugazza et alii, 2003). Current work is measuring the impact of the PFU and the reform to the ISF in 2018 by integrating the effects of these measures on amounts of wealth and dividends.

Detailed Documentation and an Open Source Model

INES is the first microsimulation model based on representative data to have entered the open source era: since 2016, the model’s source code and documentation are publicly available online on the ADULLACT (Association des développeurs et utilisateurs de logiciels libres pour les administrations et les collectivités territoriales) website (see Ouvrir dans un nouvel onglethttps://adullact.net/projects/ines-libre).

Access to data from the ERFS remains strictly controlled due to the fiscal data included. However, anyone with this right of access can now use the model to carry out studies or evaluate reforms. This openness gives the model “a central position that is demonstrated, for example, by its use by the OFCE” (Legendre, 2019). Indeed, the OFCE is one of the very first users of the model and heralded this availability in 2017 as a “silent revolution in official statistics” (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletMadec and Timbeau, 2017).

The richness of the documentation is key: both the development team and the open source users must be able to understand the model and be aware of the quality of its results in regards with the measures studied.

At the end of the update period, the development team produces a validation note for the stabilised version of the model. This version is also referred to as the “fixed” model for the legislation year that has just been incorporated. Thanks to this “fixed” version, or tag in the vocabulary of version management tools, the constant evolution of the model does not hinder the reproducibility of the results This is particularly useful, as the figures must be reproducible with a certain degree of consistency from week to week or even year to year.

The annual validation note provides an overview of the model’s strengths and weaknesses: in particular, it compares the model’s outputs with the number of benefit recipients and the amounts provided or paid, obtained from external sources and called “external targets”; the latter are corrected to a field equivalent to that of the ERFS.

The results of the simulations are not “aligned” with the external sources, which makes it possible to judge their quality. It is thus shown that simulations for income tax, family benefits, housing benefits or the prime d’activité are very close to the targets, while simulations for the allocation aux adultes handicapés (AAH) or benefits for young children (CMG, PrePare, AEEH) are of lower quality. In most cases, measures are simulated with less precision because they are aimed at a very specific population that the data does not identify perfectly. This is particularly true in the case of the allocation aux adultes handicapés.

More general documentation for the model can be found by registered users on the ADULLACT website in a “wiki” specific to the INES model. In addition, each development of new modules or new transfers simulated in INES gives rise to working papers documenting the method and results of those additions.

Recurring Uses of the INES Model

Since the mid-nineties, the expansion of the INES team and the progressive enrichment of the model through the addition of new modules able to expand the simulations have led to a diversification of uses and publications related to the model. Five important uses of the INES model are detailed below. The first three focus on an analysis of the tax and benefit system as it exists or of the effect of reforms that have taken place (ex-post analysis), while the next two are used to study the effects of avenues of reform or fictitious reforms (ex-ante analysis). Two examples of more selective studies are also presented in Box 3.

Box 3. Two Examples of Original Studies based on INES

Here, we present two original and selective studies carried out based on INES, which answer economic questions that supplement the usual static redistributive analyses that have been developed previously.

INES was used to evaluate the Effective Marginal Tax Rates (EMTR) in 2014, which are a measure of incentives to work (Fourcot and Sicsic, 2017). To calculate the EMTRs, it must be possible to measure the effect of an increase in income on tax and benefit transfers, which requires the use of a microsimulation model. INES is used to simulate the social benefits and taxes of each household, first in the counter-factual situation, then in a fictitious situation in which incomes are increased. (Sicsic, 2018) extended the analysis by also calculating the monetary gains – or incentives – linked to returning to work (based on tax rates on return to work) over a long period of time, back to the late 1990s. The study shows that marginal rates have decreased for very low incomes but increased for higher incomes and that return-to-work rates have decreased throughout the first third of the distribution. The profile of marginal rates in accordance with income level has evolved from a U to a tilde. This study forms part of a series of microsimulation-based analyses of TMEPs initiated in France by (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBourguignon, 1998) and carried out internationally (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletJara and Tumino, 2013).

INES has also been used to evaluate the redistributive effects of VAT, in both the short and medium term (André and Biotteau, 2019). It is well established that VAT is an anti-redistributive tax in static simulations (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAndré et alii, 2016). The innovative aspect of this study is that it takes second-round effects into account, which are generally not analysed. Indeed, an initial increase in VAT rates is reflected in the same year by an increase in the prices of products that are subject to VAT while, subsequently, salaries and other incomes partially adjust, as do the schedules for social benefits. Based on INES, the authors simulate VAT and the direct and indirect effects. This work requires, in particular, simulating the effect of changes in the schedules linked to revaluations. The authors show that VAT remains a slightly unequal tax in the medium term, despite the offsetting effects linked to income revaluations.

- How does the Tax and Benefit System Redistribute and Reduce Inequalities?

One of the main objectives of the INES model is to describe the redistribution performed by the tax and benefit system. Since the start of the twenty-first century, an annual overview of the redistribution has been published in the INSEE publication “France, Social Portrait”. The amounts of the various transfers per decile of living standards are indicated therein, as well as disposable income before and after redistribution, which makes it possible to quantify the reduction in inequalities due to the tax and benefit system. Thus, in 2018, the poorest 10% of the population have average living standards before redistribution of €3,290 per year, compared to €73,130 for the wealthiest 10%, i.e. 22 times more (INSEE, 2019). After redistribution, this ratio is reduced to 5.6 times more.

This redistribution assessment also makes it possible to calculate the contribution of each transfer to the reduction of inequalities. It is thus shown that, although social benefits represent monetary transfers corresponding to half the amount of the taxes, in 2018 they account for 63% of the reduction in inequality due to their targeting of the poorest, compared to 37% for taxes.

The advantage of a microsimulation model for the analysis of redistribution is threefold, it makes it possible to:

(i) carry out redistribution assessments over a long period, as has been the

case in the past

with the INES model: see (Murat et alii, 2001) for the period 1990-1998, (Amar et alii, 2007)

for the period 1996-2006, and (Eidelman et alii, 2013) for the period 1990-2010;

(ii) take into account transfers not present in the ERFS data:

for example, the non-contributory social security contributions in the usual analysis, the impôt sur la fortune, and even a broader scope from redistribution to health

cover or education in some publications (Amar et alii, 2008);

(iii) provide more recent results than the ERFS data based on previous years.

- What are the Effects of the Tax and Benefit Reforms Implemented Each Year on Inequality?

The previous application provides an overview focused on the field of tax and benefit transfers relevant to the redistribution analysis. One may also wish to analyse the effect of all legislative and regulatory changes on household living standards and on various inequality indicators.

To that end, every year since 2014, INSEE and DREES have published a redistribution and budget assessment for the new tax and benefit measures that came into force the previous year in the review France, Social Portrait. The assessment includes the same analysis of the measures implemented in the year preceding publication (for example, for 2018 in the 2019 edition of the publication; (Biotteau et alii, 2019)) stemming from the initial and amending laws on finance and the funding of the social security system, as well as decrees and national inter-professional agreements..

The principle of this evaluation is to compare the disposable income obtained with the new legislation against a so-called “counter-factual” legislation, if no legislative change had occurred during the year. The difference between the actual situation and the counter-factual situation corresponds solely to the effect of the reforms, regardless of any changes in the economic outlook that may have taken place at the same time and the effects of reforms decided on previously. The comparison makes it possible to identify households whose living standards rise or fall as a result of the reforms and to describe them according to their position in the scale of living standards or employment status. It also makes it possible to measure the effect of each measure on public finances.

The measures taken into account are the direct changes to the way transfers are calculated, allowing for a shift from “gross” income to disposable income. Indirect taxes are taken into account in some analyses.

- How Can Inequality and Poverty be Measured more Quickly?

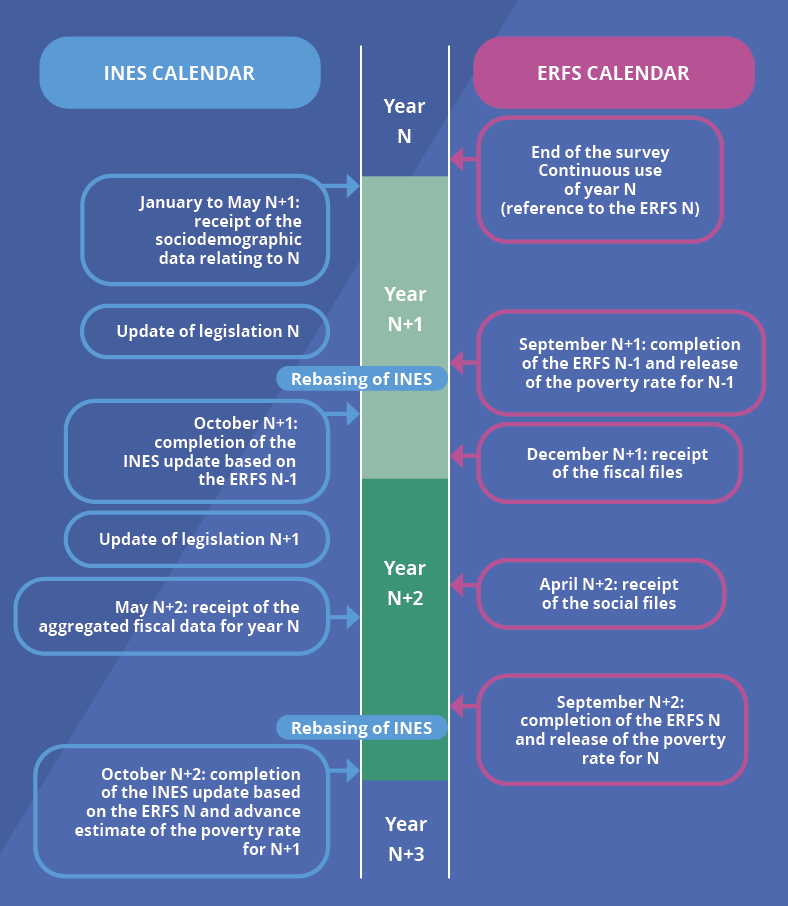

Based on the ERFS, INSEE publishes the poverty rate and the main indicators for inequalities in living standards for year N in September of year N+2. In order to more rapidly assess the effectiveness of public policies to combat poverty and inequality, INSEE is using an INES-based method, known as “nowcasting”, to produce the advanced indicators for year N in autumn of N+1 (Figure 3).

Thus, the 2018 poverty rate was estimated in October 2019 (Cornuet and Sicsic, 2019). The exercise is more global than the previous one, it takes into account not only the reforms implemented but also the evolution of the economic situation, the usual revaluations or the effect of earlier reforms. This method is also used by Eurostat for advance publications of inequality indicators or by academics (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGasior and Rastrigina, 2017).

To carry out this exercise, the ERFS of year N is used first to simulate year N, then to simulate year N+1 (legislation and evolution of the different types of income between N and N+1) (Note). The evolution of the indicators between N and N+1 which is published is, therefore, based on the use of a single version of the ERFS. The method thereby gains in robustness, as it makes it possible to overcome sampling errors from one version of the ERFS to the next. This is the fifth year that INSEE has published this advance estimation exercise and the results have always been very close to the final results published one year later (Fontaine et Sicsic, 2015).

- What is the Effect of an Increase or Decrease in Tax and Benefit Transfers?

As indicated by (Legendre, 2019), one of the important outputs of microsimulation models is the ability to simulate fictitious tax and benefit reforms.

Since 2018, INSEE has been making available, for the first time in France, simulations of fictitious tax and benefit reforms based on the INES model. It simulates the effect of fictitious rises and falls of 1%, 3% and 5% in the main transfers on household living standards per decile, inequality, public finances and the beneficiaries of the transfers (see Fontaine and Sicsic, 2018 for the methodology). This shows, for example, that a 5% increase in the flat rate of the RSA would reduce the poverty rate by 0.1 percentage points, reduce poverty intensity by 0.7 percentage points and cost €850 million in public finances. These simulations are released in a publication and a file presenting all of them (Cornuet and Sicsic, 2019).

The nature of the exercise is different from the annual assessment of the effects of tax and benefit reforms: the effects are calculated on the basis of fictitious measures, defined in a theoretical way, and not on measures that have actually come into force; however, the results of both exercises are consistent.

- Helping Public Policy Decision-Making and Evaluation

The INES model is regularly used at the request of government departments or organisations responsible for the evaluation of public policies (Parliament, the High Council for Family, Childhood and Old-Age, the Court of Auditors, the evaluation committee on taxation of capital, the expert group on the minimum wage, etc.), i.e. before deciding on its implementation. This use meets one of the main objectives the INES model has had since its creation, and it continues each year to represent an important part of the work produced by the development teams, particularly at DREES.

Recently, the model has been used a great deal to respond to the social emergency of the gilets jaunes movement. In December 2018, DREES has simulated several avenues of reform that would make it possible to focus the aid announced by the President of the Republic (€100 per month) on the targeted population (employees on the minimum wage). This work contributed to the decision in favour of an increase in the individual bonus of the prime d’activité. The teams were again called upon when the National Assembly evaluated this reform in the summer of 2019.

INES has also been used for almost three years to provide technical insight into the consequences of merging certain benefits and statutory minimum incomes. This project for the merger of means-tested benefits (RUA) is still under investigation at the time of writing.

This work requires a very precise simulation of the transfers that are the subject of the reform and, therefore, contributes to improving the model. They are usually published in the form of notes appended to the public reports.

Are the Sources Used by INES to be Expanded?

A great strength of the INES model is the experience accumulated since its creation more than 20 years ago. The model has been used to develop or change many tax and benefit transfers affecting household living standards and has therefore been constantly improved to simulate those transfers as precisely as possible. The uses of the model have diversified over the years and the model is used today, beyond the traditional analysis of redistribution, to provide advance estimates of inequality indicators and to evaluate previous reforms, or shed light on planned reforms and reforms that could take place. These applications are also an opportunity to expand and improve the model.

Bolstered by this experience, the INES model is based on extensive documentation, which is a guarantee of its reliability. One of the assets of INES, which ensures the accuracy of the simulations, is linked to the data used, in particular the very rich information from the Labour Force survey. However, this is also one of its limitations, as the survey sample sizes on which the model is based are small and do not make it possible to provide results for small sub-populations. The new comprehensive government databases that are being made available to official statistics should be a source of improvement in this respect in the long term. These data, particularly the monthly DSN data, could also improve understanding of infra-annual trajectories and incomes. This could make it possible to improve the accuracy of the simulation of certain transfers for which an understanding of the income trajectories is essential, in a context in which the tax and benefit system is evolving to take into account resources in a more “contemporary” (Note) manner. An amendment to the ageing method, which is not very well suited to large-scale economic crises such as the one caused by COVID-19, could also be an area for development of the model. This is enough to predict a long future for the INES model!

Paru le :15/09/2022

INES is the acronym of “INSEE-DREES”, the two bodies that jointly develop the model: CNAF has also co-managed the model with INSEE and DREES since 2016 (Box 1).

See the article by Didier Blanchet in the same issue for a general discussion on microsimulation models.

The Research, Studies, Evaluation and Statistics Directorate of the French Ministry of Health and Solidarity.

(Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletBessis and Cotton, 2019) detail the role of the INES, SAPHIR (Directorate-General of the Treasury) and MYRIADE (CNAF) microsimulation models in the creation of the RSA.

For the social security benefits, the family profile is often different from that of the household (the terms “home RSA” or “home prime d’activité” are used). For the sake of simplicity, in this article we only discuss households.

Social security contributions and taxes are simulated by applying the legislation to a gross income, which is reconstituted based on net income and contribution and levy rates.

Housing tax is directly included in the ERFS data and property tax is not simulated.

i.e. family benefits, family support allowance, educational allowance for disabled children, prime de naissance (a benefit following the birth of a child) and allocation de base de la prestation d’accueil du jeune enfant (an early childhood benefit), complément familial (a benefit for families with 3 or more dependent children), allocation de rentrée scolaire (a benefit for education expenses) and complément libre choix d’activité (a benefit to offset the cost of working less due to childcare).

i.e.revenu de solidarité active (a statutory minimum income), allocation aux adultes handicapés (a benefit for disabled adults), allocation supplémentaire d’invalidité (a supplementary disability benefit), allocation de solidarité aux personnes âgées (a solidarity benefit for the elderly), allocation de solidarité spécifique (an additional unemployment benefit) and garantie jeune (since 2017).

i.e.allocation personnalisée d’autonomie (a benefit for independence among the elderly), supplementary universal healthcare coverage and cheques to help pay for supplementary healthcare coverage (Sireyjol, 2016) and energy cheques or secondary education grants.

These programs are encoded in SAS. Migration of the model to an open source version using programming language R is in progress.

A household’s standard of living corresponds to its disposable income in relation to a number of consumption units, making it possible to take into account household composition and economies of scale.

To achieve this, a traditional marginal calibration weighting method is used.

These two stages are themselves linked: the calibration weighting is taken into account in the individual income evolution stage.

The model does not simulate transitions between employment statuses (for example, between employment and unemployment), as other models do, such as EUROMOD.

Differentiation is made between around thirty different income types.

For example, the ACEMO survey for employees, which makes it possible to take into account the socio-professional category and sector of activity of each of the employees.

The Observatoire français des conjonctures économiques (French Economic Observatory) is an independent organisation for research, forecasting and evaluation of public policies created by the French government in February 1981, within the Fondation nationale des sciences politiques (National Political Science Foundation).

This was notably the case for the simulation of the CMU-C and the ACS Cheques (Sireyjol, 2016), of indirect taxes (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAndré et alii, 2016) and of the ISF and IFI (Paquier et alii, 2019).

In the overview of the publication until 2014, then in the “Monetary redistribution” sheet afterwards.

See (André et alii, 2015) for the decomposition method.

Contrary to other publications (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletGuillaud et alii, 2019), only non-contributory tax and benefit transfers are taken into account in the redistribution analysis.

The delayed assessment is of good quality because in autumn N+2, the vast majority of framing data are available for N+1. See (Fontaine and Fourcot, 2015) for further details on the method.

Address to the nation by the President of the Republic on December 10th 2018, announcing measures in response to the economic and social emergency, including a €100 increase in revenue for people earning the minimum wage.

Such as the Fidéli (Fichiers démographiques sur les logements et les individus – Demographic files on housing and individuals) databases produced by INSEE, or the Déclaration Sociale Nominative (Nominative Social Declaration – DSN).

This is the case in respect of the reform of the withholding of income tax, or the coming reform on “contemporising” resources for the calculation of housing benefit, i.e. using income from the past quarter as a basis, instead of that from N-2.

Pour en savoir plus

ALBOUY, Valérie, BOUTON, François, LE MINEZ, Sylvie et PUCCI, Muriel, 2003. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLe modèle de microsimulation INES : un outil d’analyse des politiques socio-fiscales. In : Dossiers solidarité et santé. La microsimulation des politiques de transferts sociaux et fiscaux à la Drees : objectifs, outils et principales études et évaluations. [online]. July-September 2003. N°3, pp. 23-43. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

AMAR, Élise, MARICAL, François, LAIB, Nadine et MIROUSE, Benoît, 2007. 1996-2006 : 10 ans de réforme du système de redistribution. In : France Portrait social, édition 2007. [online]. 1er November 2007. Collection Insee Références, pp. 81-97. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

AMAR, Élise, BEFFY, Magali, MARICAL, François et RAYNAUD, Émilie, 2008. Les services publics de santé, éducation et logement contribuent deux fois plus que les transferts monétaires à la réduction des inégalités de niveau de vie. In : France, portrait social, édition 2008. [online]. 1er November 2008. Collection Insee Références, pp. 85-101. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

ANDRÉ, Mathias et BIOTTEAU, Anne-Lise, 2019. Effets de moyen terme d’une hausse de TVA sur le niveau de vie et les inégalités : une approche par microsimulation. [online]. 11 February 2019. Insee, Documents de travail, n°F1901-G2019/01. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

ANDRÉ, Mathias, BIOTTEAU, Anne-Lise et DUVAL, Jonathan, 2016. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletModule de taxation indirecte du modèle Ines – Hypothèses, principes et aspects pratiques. [online]. November 2016. Drees, Documents de travail, Série Sources et méthodes, n°60. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

ANDRÉ, Mathias, CAZENAVE, Marie-Cécile, FONTAINE, Maëlle, FOURCOT, Juliette et SIREYJOL, Antoine, 2015. Effet des nouvelles mesures sociales et fiscales sur le niveau de vie des ménages : méthodologie de chiffrage avec le modèle de microsimulation Ines. [online]. 8 December 2015. Insee, Documents de travail, n° F1507. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

BACH, Laurent, BOZIO, Antoine, FABRE, Brice, GUILLOUZOUIC, Arthur, LEROY, Claire et MALGOUYRES, Clément, 2020. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDes analyses fiscales simplistes ? [online]. 28 February 2020. Le blog des économistes de l’IPP. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

BESSIS, Franck et COTTON, Paul, 2019). Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletModèles de microsimulation et monopole de l’expertise économique : de nouveaux rapports entre gouvernants et gouvernés ? In : L’État des économistes. La science économique face à la puissance publique (XXe-XXIe siècles). [online]. November 2019, Amiens, France. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

BIOTTEAU, Anne-Lise, FREDON, Simon, PAQUIER, Félix, SCHMITT, Kévin, SICSIC, Mickaël et VERGIER, Noémie, 2019. Les personnes les plus aisées sont celles qui bénéficient le plus des mesures socio-fiscales mises en œuvre en 2018, principalement du fait des réformes qui concernent les détenteurs de capital. In : France, portrait social, édition 2019. [online]. Collection Insee Références, pp. 133-155. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

BOURGUIGNON, François, 1998. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletFiscalité et redistribution. [online]. Rapport du Conseil d’Analyse Économique n°11, Éditions La Documentation française. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

CORNUET, Flore et SICSIC, Michaël, 2019. Estimation avancée du taux de pauvreté et des indicateurs d’inégalités. En 2018, les inégalités et le taux de pauvreté augmenteraient. [online]. October 2019. Collection Insee Analyses, n°49. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

DAVID, Marie-Gabrielle, LHOMMEAU, Bertrand et STARZEC, Christophe, 1999. Le Modèle de Microsimulation INES. [online]. August 1999. Insee, Documents de travail, n°F9902, tome 2. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

EIDELMAN, Alexis, LANGUMIER, Fabrice et VICARD, Augustin, 2013. Prélèvements et transferts aux ménages : des canaux redistributifs différents en 1990 et 2010. In : Économie et Statistique. [online]. 29 August 2013. Insee, n°459, pp. 5-26. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

FONTAINE, Maëlle et FOURCOT, Juliette, 2015. Nowcasting du taux de pauvreté par la micro-simulation. [online]. December 2015. Insee, Documents de travail, n°F1506. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

FONTAINE, Maëlle et SICSIC, Michaël, 2015. Des indicateurs précoces de pauvreté et d’inégalités - Résultats expérimentaux pour 2014. [online]. 23 December 2015. Collection Insee Analyses, n°23. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

FONTAINE, Maëlle et SICSIC, Michaël, 2018. L’effet d’une variation du montant de certains transferts du système socio-fiscal sur le niveau de vie : résultats sur 2016 à partir du modèle de microsimulation Ines.(Cahier de variantes). [online]. 30 August 2018. Insee, Documents de travail, n° F1806. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

FOURCOT, Juliette et SICSIC, Michaël, 2017. Les taux marginaux effectifs de prélèvement pour les personnes en emploi en France en 2014. [online]. February 2017. Insee, Documents de travail, n°F1701. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

FUGAZZA, Marco, LE MINEZ, Sylvie et PUCCI, Muriel, 2003. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletL’influence de la PPE sur l’activité des femmes en France : une estimation à partir du modèle Ines. In : Économie et prévision. [online]. n°160-161, pp. 79-102. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

GASIOR, Katrin et RASTRIGINA, Olga, 2017. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletNowcasting: timely indicators for monitoring risk of poverty in 2014-2016. [online]. 10 May 2017. EUROMOD Working Paper Series EM7/17. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

GUILLAUD, Elvire, OLCKERS, Matthew et ZEMMOUR, Michaël, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletFour levers of redistribution: The impact of tax and transfer systems on inequality reduction. [online]. 13 January 2019. The Review of Income and Wealth. DOI : 10.1111/roiw.12408. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

INSEE, 1998. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLes modèles de microsimulation. In : Économie et Statistique / Economics and Statistics. [online]. September 1998. N°315, pp. 29-116. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

INSEE, 2019. Fiche 4.4 Redistribution monétaire. In : France, portrait social, édition 2019. [online]. 19 November 2019. Collection Insee Références, pp. 200-201. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

JARA, H. Xavier et TUMINO, Alberto, 2013. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletTax-benefit systems, income distribution and work incentives in the European Union. In : International journal of microsimulation. [online]. N°6(1), pp. 27-62. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

LEHMANN, Étienne, MARICAL, François et RIOUX, Laurence, 2013. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletLabor Income Responds Differently to Income-Tax and Payroll-Tax Reforms. In : Journal of Public Economics. [online]. 16 October 2012. Vol. 99, pp. 66-84. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

LEGENDRE, François, 2019. L’émergence et la consolidation des méthodes de microsimulation en France. In : Économie et Statistique / Economics and Statistics. [online]. 18 December 2019. N°510-511-512, pp. 207-220. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

MADEC, Pierre et TIMBEAU, Xavier, 2017. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletStatistique publique : une révolution silencieuse. [online]. Le blog de l’OFCE. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

MURAT, Fabrice, ROTH, Nicole et STARZEC, Christophe, 2001. L’évolution de la redistributivité du système socio-fiscal entre 1990 et 1998 : une analyse à structure constante. In : France, portrait social, édition 2000-2001. V. 2000/01. pp. 133-150. ISSN : 1279-3671.

PAQUIER, François, SCHMITT, Kévin, SICSIC, Michaël, 2019. Simulation des effets redistributifs de la transformation de l’ISF en IFI à l’aide du modèle Ines. [online]. 18 December 2019. Insee, Documents de travail, n°F1908. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

SICSIC, Michaël, 2018. Les incitations monétaires au travail en France entre 1998 et 2014. In : Économie et Statistique / Economics and Statistics. [online]. 10 January 2019. N°503-504, pp. 13-35. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

SICSIC, Michaël, 2019. Les incitations fiscales au travail et à la R&D et leurs effets sur le marché du travail. Paris : École doctorale des sciences économiques et gestion, sciences de l’information et de la communication. Thèse de doctorat de sciences économiques.

SIREYJOL, Antoine, 2016. La CMU-C et l’ACS réduisent les inégalités en soutenant le pouvoir d’achat des plus modestes – Impact redistributif de deux dispositifs d’aide à la couverture complémentaire santé. [online]. October 2016. Les Dossiers de la Drees, n°7. [Accessed 20 April 2020].

THÉLOT, Claude, VILLAC, Michel, 1998. Politique familiale – Bilan et perspectives. Rapport à la Ministre de l’emploi et de la solidarité et au Ministre de l’économie, des finances et de l’industrie. 22 July 1998. Paris, Éditions La Documentation française. ISBN : 978-2-11-090989-7.