Courrier des statistiques N3 - 2019

IESS: Europe Harmonises its Social Statistics to Better Inform Public Policies

Adopted in 2019, the IESS (Integrated European Social Statistics) framework regulation is the result of a long process aimed at modernising European statistics. To support ambitious social policies, statistics must always seek to meet the needs of both policy makers and the public in better ways, combining comparability, accuracy, flexibility, timeliness and cost-effectiveness. Previously, each survey stemmed from a specific regulation or informal agreement. IESS sets out a coherent and integrated framework for all surveys, thereby improving the comparability of Member States’ statistics. INSEE is striving to adapt to these new requirements with a programme of incremental reforms to its social surveys, a larger proportion of which will now be governed by European rules. As well as the changes brought about by IESS (multi-annual programming, common concepts, sampling, questionnaires), other changes are also underway, including the development of mixed-methods approaches. Once the initial investments have been made, the production costs associated with these data should be better managed, provided appropriate tools are developed. Lastly, attention will need to be paid to a wider audience than just decision-makers, both in terms of the common good and the response burden.

- A Bit of History – Or the Long Road to a Framework Regulation

- The Innovations Introduced by IESS: a Global Vision of Social Statistics...

- ...Sharing of Concepts...

- ... And Several Other Harmonisations

- Box. The Precision Thresholds of Surveys Set by European Regulations in the Case of France

- Consequences: Increased Weight of “European” Surveys

- ...Adjusting the Sample Design...

- … And Shorter Deadlines

- Towards Greater Coherence and Comparability Between Countries?

- Meeting Needs Better?

- Towards More Cost-Effective Official Statistics?

Social indicators – whether relating to poverty, young people leaving education without qualifications or unemployment – are widely used by decision-makers, researchers and the general public alike to understand and assess changes in European society over time and space and to set targets for action. Their relevance and quality, particularly in terms of the scope for comparing different countries, but also in terms of consistency, accuracy and timeliness, are therefore important factors. The European system of social statistics, which is the basis for their production, has been built up incrementally, topic by topic, and by first setting targets in terms of variables to be produced within the scope of regulations or informal agreements specific to each survey. The objective of the new framework regulation on integrated social statistics was to further harmonise the production of social statistics upstream between the different social surveys conducted by the national statistical institutes, with a specific focus on concepts and, in some cases, on the methods used.

A Bit of History – Or the Long Road to a Framework Regulation

Adopted in April 2019, the IESS (Integrated European Social Statistics) framework regulation is the first result of a long process aimed at modernising European social statistics initiated at the end of the 2000s as part of the “ESS Vision 2020”, the European strategy for 2020.

Adopted in 2009, the “European Statistical Law” laid down the basic principles and rules for how the European Statistical System should be organised (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEurostat, 2010), and a first test run of the programme of social surveys was also drawn up at the time. The way was paved for the preparation of framework regulations designed to structure the production of entire sections of the reformed European Statistical System. Reflection on the need for enhanced coherence of the content and methods of the two main “pillars” of social surveys (the Labour Force Survey and the EU-Statistics on Income and Living Conditions instrument), the first step towards the “integrated” vision set out as part of IESS, began in 2010.

In 2011, the directors of European national statistical institutes adopted, on a proposal from Eurostat, a project on the modernisation of social statistics designed to support ambitious social policies (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletEurostat, 2011). The project also aimed to be cost-effective and flexible to ensure new needs can be met rapidly while maintaining high quality statistical outputs amid increasing budgetary pressures and greater competition in data production.

The “Wiesbaden” memorandum laid the foundations of IESS, i.e. a common and standardised architecture for social statistics built around a series of surveys conducted periodically among a sample of persons or households, supplemented by a better use of administrative data. Specific reference was made to the need for high-quality data on the living conditions of subgroups of the population (including children, migrants and elderly), to the Time Use and Household Budget surveys and to the need for stronger links with national accounts. The memorandum also makes reference to the need for appropriate funding, commensurate with the investments required at a time of budgetary constraints.

The modernisation programme as a whole also included a draft regulation on censuses and population statistics. In the longer term (beyond 2020), a third framework regulation was also envisaged to provide a legal basis for the statistical production of administrative data in various domains (employment, health, social protection, education, crime, etc.) as well as sectoral accounts.

The foundations for the modernisation programme were adopted by the committee of Directors-General of the National Statistical Institutes at the end of 2014, when the process of preparation of the Regulation was formally launched. The process included a web-based public consultation in 2015. The co-legislative process – a structurally long process since the Parliament and the Council must reach a consensus on a proposal from the Commission – lasted several years, and the regulation was adopted in the last days of the European Parliament’s mandate in April 2019, ahead of effective implementation in 2021 (European Parliament, 2019).

The Innovations Introduced by IESS: a Global Vision of Social Statistics...

Prior to IESS, social statistics collected from households were based on an “organ pipe” approach – i.e. on a “one survey, one regulation” basis. In addition, in some cases, no legislation existed, meaning that some surveys would be transmitted to Eurostat on a voluntary basis by the Member States conducting them.

This was the case, for example, of the Household Budget survey or the Time Use survey, but also the first edition of the Health surveys, conducted between 2006 and 2009 depending on the country. In addition, the survey system has been built up incrementally, with the oldest regulation relating to the Labour Force Survey (1998). The coherence of the various texts was bound to suffer as a result.

Lastly, the framework regulation will replace or amend existing legislative regulations on:

- the Labour Force Survey, as well as all the implementing measures (i.e. implementing and delegated acts) relating to each of the thematic modules developed to complement the survey (known as ad hoc modules);

- Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (SILC);

- the Adult Education Survey (AES);

- the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS);

- and the Survey on information and communication technology (ICT) usage.

Each survey will nonetheless continue to be subject to dedicated implementing measures, including a specific implementing act and a delegated act. The main novelty introduced by IESS is that it provides a coherent and integrated framework for all surveys, with global multi-annual programming and common concepts.

Within this common framework, the scope of the themes included in the Regulation has been broadened. Seven domains are now covered: the labour market, resources and living conditions, health, education and training, information and communication technologies usage, time use and consumption. The latter two had not previously been the subject of regulations and the labour market domain includes legal support for the production and publication of monthly aggregate unemployment rates, for which data had previously been transmitted on the basis of informal agreements. While a number of important topics are not covered, including the housing market and security, and while Time Use Surveys are still only included on an optional basis, the scope of European social statistics is significantly broadened as a result.

A multi-year programme of surveys running for eight years has been defined. One major request from Member States was to have a multi-annual vision of their commitments and to ensure that the necessary structures and resources could be put in place in good time. Multi-annual surveys (former ad hoc modules of the Labour Force Survey and EU-Statistics on Income and Living Conditions) are incorporated into the programme and many of their themes have been pre-defined.

...Sharing of Concepts...

Extensive work has been conducted to define and standardise the variables common to different surveys. The work undertaken covers a wide list of variables, whether they are collected in all surveys (basic variables) or only in some of them. Technical manuals specify and detail the content of each of them. This is a real step towards better comparability between countries and between surveys and comes as a result of a significant amount of collective preparatory work undertaken with all countries as part of the thematic working groups.

The new regulation and its implementing measures (or complementary texts) also introduce the concept of housekeeping unit, defined as persons living at the same address and sharing their resources or expenses. Housemates who do not share their resources are treated as separate households. This definition was already in use for income and consumption surveys but was not applied in domains such as the Labour Force Survey. It has now been defined as a target for all surveys which scope remains ordinary households.

As regards the content of surveys, the implementing acts set out in detail the variables to be provided as well as their periodicity, while the various methodological documents accompanying the legislative texts provide the key definitions. It is important to note that these surveys give rise not only to the transmission of aggregate data but also to individual and anonymised micro-data sent to Eurostat. These can be reused by authorised researchers in accordance with the provisions of the “European Statistical Law”. In most cases, the survey process required to arrive at these variables remains, as it was previously, the responsibility of Member States, as does the method of data collection – i.e. direct surveys, whether by telephone, face-to-face or online, administrative data or even small area estimates for local data – subject to compliance with the quality criteria defined in the “Statistical Law” (Regulation EC/223/2009, Article 12) and detailed in the European Statistics Code of Practice (Eurostat, CSSE, 2017).

... And Several Other Harmonisations

One notable exception is the Labour Force Survey, which will go further towards harmonisation through inputs. In this case, a common mandatory questionnaire structure (or flowchart) was developed for the core of the survey, namely the module for determining activity status as defined by the International Labour Office (ILO). Here, the use of administrative data is prohibited. Previously, there was already a requirement to collect one “ILO module” per survey, but its content was under the responsibility of Member States. This approach is essential to ensure better comparability between countries in a domain where administrative data differ conceptually from the criteria used by the ILO (Coder et alii, 2019).

Annex II of the Framework Regulation provides a unified definition of the precision (or accuracy) requirements to which surveys must adhere for certain key indicators (see box). A number of precision requirements have been defined at the regional level. Precise technical specifications are given on the sampling frames to be used to produce random samples across the entire scope of households, and Annex III specifies the rotational sample design required for the Labour Force Survey. The rotational period for Statistics on Income and Living Conditions is also set at a minimum of 4 years.

Annex V of the Framework Regulation lays down legally binding data transmission deadlines to Eurostat in each domain, and reporting on the quality of surveys is based on the standardised structure of the quality reports and the metadata documentation standard defined in conjunction with the quality experts of different countries (Eurostat, 2015).

Lastly, a flexibility clause allows Eurostat to partially modify the content of surveys by means of delegated acts designed to meet new needs. The clause – which was much debated with the Member States, who saw it as leading potentially to rising costs – is, however, subject to the requirement that no significant additional burden is imposed, that a feasibility study be conducted and, above all, that a threshold governing modified content be adhered to (i.e. no more than 5% of the detailed topics over a period of four years for the Labour Force Survey and SILC and no more than 10% between two editions for other surveys). Similar requirements apply to the number of variables. The directors of the National Statistical Institutes, shall be consulted by Eurostat as experts on the delegated acts before their adoption.

Box. The Precision Thresholds of Surveys Set by European Regulations in the Case of France

The IESS Regulation sets precision thresholds to be met by countries in developing indicators, particularly those linked to the labour market and poverty. They relate to six indicators.

First, there are three quarterly estimates related in each case to the population aged 15-74: the number of employed persons, the number of unemployed persons and the number of unemployed persons at the regional level (NUTS 2).

There are also three indicators relating to income and living conditions: the AROPE* indicator of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion at both national and regional levels and, lastly, the 4-year persistent poverty rate at the national level.

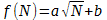

The precision thresholds set out in the annex to the Framework Regulation are expressed using a formula that sets a maximum value for the standard deviation of the indicator. The formula is as follows:

Here, “̂p”

is the value of the indicator and

, where N is the size of the domain (country or NUTS-2) and a and b are the parameters defined for each indicator.

The expression of the formula may seem strange to statisticians: the denominator of the fraction should not be a function of the size of the population of interest (N), but of the size of the selected sample (n).

However, by adopting a square-root form for f for the size of the population of interest (N), for large values of N the dependence on this size is limited to what it would be if the principle of proportional allocation were applied. In addition, a specific formula is provided for in the case of the proportion of unemployed persons for regions with fewer than 300,000 inhabitants. However, the values of parameters a and b, defined separately depending on whether they apply at the national or NUTS-2 level, may lead to inconsistency between the precision requirements for each of the different levels.

Thus, with the thresholds set in the Regulation based on the previous formula, the number of respondents required to meet the national threshold for the share of unemployed persons is, in the case of metropolitan France, 109,400. However, the number of respondents required to meet all regional thresholds is 83,000, or a 31% decrease. In the case of the AROPE indicator, the deviation is 48%, but in the opposite direction. Given this, it seemed sensible to use the less costly “small area estimation” method based on the national survey and on complementary modelling (Rao et Molina, 2015; Sautory, 2018). This possibility was eventually incorporated into the framework regulation at the request of France.

* This indicator, known by its acronym AROPE (standing for At-Risk Of Poverty or social Exclusion), corresponds to the sum of persons who are either at risk of poverty, or severely materially deprived or living in a household with a very low work intensity. It is the main indicator used to monitor the poverty reduction target included in the Europe 2020 strategy.

N.B.: the detailed analysis carried out for the purposes of this box was conducted by Patrick Sillard and Martin Chevalier (INSEE, Department of Statistical Methods).

Consequences: Increased Weight of “European” Surveys

INSEE has given its full support to the draft framework regulation in seeking to achieve greater integration and standardisation, reflecting the recommendations made by the French National Council for Statistical Information on the international comparability of data. Our pre-existing system of surveys was still well adapted to the new regulation, even if, as will be seen below, the new provisions have required significant investments.

With the extension of the scope of the framework regulation and the precise definition of a multi-year programme involving strict transmission deadlines, INSEE’s survey programme is increasingly being shaped by surveys governed by European regulations around which the other surveys conducted by its network of interviewers must be organised, including surveys on housing, working conditions, mobility and even homelessness. Date adjustments will automatically apply to the latter in a context of constrained resources and increasing user demands for new or renewed data collections (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCNIS, 2019). In the field of social statistics, the increasing use of administrative data – though central to certain domains such as income – is not sufficient to meet our need for knowledge in particular domains, such as specific situations, behaviours and opinions, poverty in living conditions and self-perceived health. Surveys remain indispensable and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future, even with the prospect of innovative big data being used (Desrosières, 2004; Tassi, 2018). It is therefore necessary to be able to continue conducting them effectively while maintaining their quality. That is why INSEE, in common with other European countries (Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletDe Leeuw, 2018), has embarked on the development of a mixed-mode survey programme built around common tools. The renewal of the Labour Force Survey, required under IESS, provides an opportunity to introduce online collection as an additional method of response in the event of re-interrogation.

...Adjusting the Sample Design...

The precision requirements imposed by the Regulation (Box) have also required a review of the current sample design, in particular to achieve the precision required at the regional level for the share of unemployed persons in the population for the Labour Force Survey. The schedule, which has already been defined for the periodic renewal of the samples used in INSEE’s household surveys, has made the work required easier to carry out. The sample used in the Labour Force Survey was due to be changed in 2019. The new master sample for other household surveys should be drawn from 2020. The new sampling frame (based on tax data rather than population censuses), together with more effective sampling methods, improved the accuracy of the data collected. The two sampling designs could then be coordinated at the level of the geographical areas making up their primary units to facilitate the data collection process in the field. In the case of the Labour Force Survey, this will be reached through an adjustment of the regional distribution of the sampling areas to best meet the regional precision requirements imposed by IESS, with the final sample size being reduced by 15%. The implications for the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions are more far-reaching, with the precision requirements and, above all, the shorter 4-year observation period meaning that the sample design will need to be changed over several years. Requirements at the regional level, which are too costly to meet by increasing the sample size for this survey, will be addressed by producing the variable used to construct the at-risk-of-poverty indicator by means of small area estimates, which will therefore have to be produced as regularly as the survey.

The most visible and rapid changes for data users will be the renewal of the Labour Force Survey and the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions and relate first to the modification of questionnaires with the aim of adapting to the commonly defined concepts and providing the detailed list of variables prescribed in the relevant implementing and delegated acts. In the case of the Labour Force Survey, the scale of the project, combined with the use of online data collection in the event of re-interrogation, will require the implementation of a pilot project in 2020, very soon after the adoption of the Regulation, particularly given the need to assess breaks in time-series and to “backcast” historical data to obtain time-consistent statistical series over previous periods. Eurostat has strongly supported these developments by granting funding to accompany the changes.

… And Shorter Deadlines

Last but not least, considerable effort will be required to produce income data more rapidly for the purposes of the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions. The Framework Regulation provides for the transmission of data at the end of the reference year and, “in exceptional cases”, for the transmission of provisional data at the end of the reference year and revised data at the end of February of the following year.

This represents a major challenge for France given the time frames for the availability of the tax and social data used to produce income data: untill now, the income figures derived from them can only be transmitted to Eurostat in September of the following year. The project involves using earlier (but less complete) disclosures of tax data to produce revised data and bridging the time lag without significantly harming the quality of the transmitted data. This will require several years of adaptation, particularly since information system changes related to the introduction of a pay-as-you-earn system will also need to be taken into account. Here too, the system of derogations included in the regulation should help to manage the transition.

Ultimately, the process of implementing the changes associated with the new Framework Regulation will be staggered over time, in line with the survey programme and the preparation of the implementing and delegated acts associated with each of them. Eurostat will provide financial support to adapt the surveys and will grant derogations where necessary to allow time for adjustments to be made. However, the deadlines for the Labour Force Survey and the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, the first surveys in the programme concerned by the new measures, are particularly tight. For the time being, the choice of collection method is a matter for each country, although Eurostat supports reflection on appropriate recommendations on these points. In France, the gradual transition to a mixed-method approach and the standardisation of survey tools will be carried out in parallel, with successive adjustments to be made. For example, unlike the Labour Force Survey, online collection has yet to be introduced for some of the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions and will be rolled out in a second phase. For its part, the Labour Force Survey is not concerned, at least in the short term, by the new tools currently being developed to produce the surveys using a mixed-method approach, which it will adopt in a second phase.

Towards Greater Coherence and Comparability Between Countries?

The standardisation of concepts and variables implemented by IESS is clearly critical to improving the comparability of data between countries. One example is actual working time: problems of comparability between countries (Körner and Wolff, 2016) should be significantly reduced once all countries adopt a fixed reference week, as provided for in the framework regulation. However, interpretations of definitions and content will need to be easy to interpret and should only provide limited scope to make local adjustments.

For example, the discussion of variables in the Labour Force Survey in the context of preparing the associated implementing legislation revealed major differences between countries in how parents on parental leave, who are also treated very differently from one country to another, were classified as being in employment or not in employment. In France, as in some other countries, the interpretation of ILO criteria previously emphasised a duration criterion: beyond three months, parents absent from work for parental leave were not considered as employed. Following discussions on the subject, a wider criterion for the existence of a link with employment eventually prevailed in IESS: parents absent from work for parental leave are considered to be in employment with no limit on the duration of leave provided they report receiving (or being eligible for) employment-related income, even if the remuneration of their parental leave is not proportional to their previous wage. In the course of the discussion, it became apparent that many countries were already doing this, despite not having been mandated to do so, thereby skewing the comparison of employment rates, especially for women. In the end, this looser definition ultimately prevailed for the European employment rate index, even if it may seem strange for a lengthy absence of mothers from the labour market to raise their children to have no impact on the female employment rate. In this particular example, there is, in other words, still room for interpretation. A detailed assessment of national provisions on parental leave and the classification of the related employment statuses is necessary to ensure full comparability. This has yet to be done.

Another example is the status of students living alone in relation to their parents’ household, with parents often providing significant financial support and students returning to live with their parents on a regular basis. If we adhere to census concepts, students living separately in an ordinary dwelling during the academic year should be surveyed separately. In income surveys, in accordance with the definition of an ‘economic’ household, it may be desirable to include them in their parents’ household when calculating standards of living that better reflect family resource sharing. However, in this case, it is generally the parents who respond on behalf of their children to interviewer. Lastly, the Regulation allows Member States to choose either option for each survey, subject to precisely documenting the chosen option.

A major trade-off left to each country is the extent to which administrative data can be used instead of survey data (with the exception of the activity module of the Labour Force Survey), as well as the choice of collection method used in surveys. It would have been unrealistic to legislate further on the matter, and indeed no Member State wanted to do so since statistical systems vary from country to country: in northern countries, a significant proportion of social data are obtained from administrative registers, and some countries still conduct surveys using paper questionnaires while others have turned to online or telephone collection methods as their preferred methods. However, research on the effects of data collection methods suggests that the response behaviour of respondents is mode-dependent, even in the case of identical surveys or questions (Vinceneux, 2018; Razafindranovona, 2015).

Lastly, while IESS will undoubtedly contribute to improving comparability, it will not be a radical and definitive solution. Rather, it represents a significant step towards a process of convergence – a process that remains incomplete, despite achieving greater harmonisation through “inputs” (variables, content) than previously.

Meeting Needs Better?

Users’ information needs, including those of public decision-makers, change over time. As we have seen, IESS allows both a degree of flexibility and room for change and development. The introduction of a multi-annual Time Use survey – a vital tool for quantifying gender balance in daily activities and for examining reconciliation between work and family life – is optional but remains a target to be achieved by all, albeit within an unspecified period. IESS also leaves room for innovation by making provision for supporting pilot studies on new methods and topics. For example, a study is currently underway on the topic of gender violence. Pilot studies may also be funded to broaden the collection of social data to include people not living in ordinary housing or hard-to-reach populations. Migrants are referred to explicitly. Feasibility studies are also being planned and funded to modernise the collection of consumption and time use data (for example). Working groups comprising volunteer countries are beginning to explore the use of anonymised credit card data and electronic diaries for this purpose. As can be seen, IESS allows for innovation, and that is a very good thing. In the end, however, everything will depend on the actual results of these experiments and on the resources that Member States will actually be able to devote to these innovations (over and above the vital financial support provided by Eurostat) and, above all, to their transition to the production stage, possibly by achieving productivity gains in other domains.

In addition, the new system of ad hoc modules integrated into the surveys at different periodicities over the eight years of the rolling programme also allows for a degree of flexibility: certain topics (for example, two out of eight in the case of the Labour Force Survey) are left free to tailor the process to the Commission’s needs, and the pace of data collection is adapted to less frequent needs.

Another question is whether data users will ultimately be satisfied. It is important to recognise that while the needs of other Commission departments are regularly explored and highlighted by Eurostat, establishing links with national users and even researchers is not so easy. The procedures and structures for consulting users remain relatively limited at the European level, and links with national commissions such as the National Council for Statistical Information in France are still struggling to gain momentum. The development of statistical literacy is also an essential condition for dialogue with non-expert users who struggle to understand the challenges of producing quality data given the deluge of so much (bad) “data” on social networks. Fortunately, this is one of the central lines of communication for Eurostat and for a large number of Member States, including France.

Towards More Cost-Effective Official Statistics?

By standardising and integrating surveys and improving the predictability of commitments in terms of data collection and transmission, IESS will undoubtedly improve how national data collections are carried out in the long run. However, while the regulation is clearly a facilitator in this respect, it does not guarantee that official statistics will become more cost-effective in the short term. The investment required to reform surveys, to carry out the small number of geographical extensions required and to shorten certain production deadlines is significant, even in a country such as France, which is already relatively close to the target model. To improve cost-effectiveness at the national level, it is important to seize the opportunities provided by IESS to share and pool data collection tools and to conduct some aspects of the collection process online. This is precisely what is happening in France with the development of a mixed-mode survey programme and its common tools, which will make ensure that interviewers are able to devote their time to data collections where they are indispensable and irreplaceable, such as complex questionnaires and those involving specific or difficult-to-reach populations (Beck and De Peretti, 2017). This is also what is being done with the implementation of a survey documentation repository, which will allow parts of questionnaires to be simply reused or for survey metadata to be produced more easily, and, for example, the standard-format quality reports developed in conjunction with Eurostat (Bonnans, 2019). But this requires time.

The flexibility provided for by IESS will also come at a cost. Changing part of the content of a questionnaire and developing new topics requires effort. That is why Member States have wanted to set limits to these adjustments. This is not the only reason: we need to be able to compare social statistics in space, but also in time. Developing and changing a survey or questionnaire always involves a trade-off between the need to adjust to a changing situation and maintaining a useful comparative view of the past. In such cases, the additional cost involves, for example, having to conduct a pilot survey to measure the magnitude of breaks in time-series.

Lastly, cost control is not only a budgetary necessity for statistical institutes. The response burden also requires special attention so as not to discourage households. The development of online surveys is therefore a response to repeated requests from some respondents and should help to limit the decrease in the response rate, particularly in the case of telephone surveys. The development of the joint use of data designed to complement surveys, whether from administrative records or other sources, must be continued, and the development of new surveys must remain reasonable. This is also one of the concerns highlighted in the discussion on IESS, and it should not be ignored.

Paru le :22/06/2021

These gentlemen’s agreements are laid out in written texts but are only binding on volunteer countries.

See Hervé Piffeteau’s paper on the legal triptych of European statistics in this issue.

Known in France as the “Enquête Emploi”.

EU-SILC (Statistiques sur les ressources et les conditions de vie, or SRCV in France).

For more details on the difference between the two types of acts, see the paper by Hervé Piffeteau in this issue.

France transmits its registered unemployment figures at month end. Eurostat produces a monthly unemployment rate based on econometric modelling using the number of persons registered at the public employment service and the Labour Force Survey. The same system will apply in the new framework regulation.

Beginning the module with a question such as “In the reference, from Monday to Sunday, have you done any work for pay or profit, even if it was only for one hour?” was one principle applied, albeit not by all countries.

At the level of the former administrative regions in France (NUTS 2 classification).

See Hervé Piffeteau’s paper on the legal triptych of European statistics in this issue.

And more broadly of the Official Statistical Service, health surveys being the responsibility of the Ministerial Statistical Office for Health (DREES).

One typical example is the status of unemployment as defined by the ILO (referred to above).

IESS extends the use of the Minimum European Health Module, set of three questions on self-perceived health status, disability and activity limitations and chronic morbidity.

It should be noted that IESS covers the entire national territory, including Mayotte, except for EU-Statistics on Income and Living Conditions. In the case of Mayotte, it will therefore be necessary to conduct a Labour Force Survey on a continuous basis instead of the annual survey conducted previously. This project will be carried out in a second phase, with Mayotte having to put in place a continuous population census at the same time. The system of derogations included in the Regulation should provide more time for the local statistical system to adapt.

Small regions are seeing their number of collection areas increase, while those in the Île-de-France region are falling.

Mandatory minimum duration defined by the regulation.

The sampled dwellings are surveyed during six consecutive quarters.

And perhaps to the future abolition of income tax returns...

These texts must be finalised at the latest one year before the survey concerned.

Explicit provision is made for such funding in the framework regulation.

In the case of the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions, the reform was scheduled for as early as 2020 because of the need to redesign the survey’s entire IT chain.

This is known as a “proxy” interview.

And of some modules of the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions instrument such as health, material deprivation and well-being.

We might also think of homeless populations, although this domain has yet to be addressed at the European level.

The online consultation process carried out by Eurostat among users in 2015 only generated around a hundred contributions, of which approximately one third were from researchers, a figure that seems relatively small when compared, for example, to the 21,330 responses to the consultation on the Law for a Digital Republic conducted in France during the same period and over a shorter duration.

Pour en savoir plus

BECK, François et DE PERETTI, Gaël, 2017. La collecte multimode à l’Insee : d’un effet de mode à un effet sur nos travaux. [en ligne]. 22 juin 2017. Séminaire de Méthodologie statistique du département des méthodes statistiques. Paris. [Consulté le 25 octobre 2019]

BONNANS, Dominique, 2019. RMéS: INSEE’s Statistical Metadata Repository. In : Courrier des statistiques. [en ligne]. 27 juin 2019. N°N2, pp. 46-55. [Consulté le 24 octobre 2019]

CNIS, 2019. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletAvis du Moyen-terme 2019-2023. [en ligne]. 1er février 2019. N°8/H030. [Consulté le 5 novembre 2019]

CODER, Yohan, DIXTE, Christophe, HAMEAU, Alexis, HAMMAN, Sophie, LARRIEU, Sylvain, MARRAKCHI, Anis et MONTAUT, Alexis, 2019. Les chômeurs au sens du BIT et les demandeurs d’emploi inscrits à Pôle emploi : une divergence de mesure du chômage aux causes multiples. In : Insee Références – Emploi, chômage, revenus du travail. [en ligne]. Édition 2019, pp. 71-85. [Consulté le 25 octobre 2019]

DE LEEUW, Edith D., 2018. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletMixed-Mode: Past, Present, and Future. In : Survey Research Methods – Journal of the European Survey Research Association. [en ligne]. 13 août 2018. Vol 12, n°2, pp. 75-86. [Consulté le 28 octobre 2019]

DESROSIERES, Alain, 2004. Enquêtes versus registres administratifs : réflexions sur la dualité des sources statistiques. In : Courrier des statistiques. [en ligne]. Septembre 2004. N° 111, pp. 3-16. [Consulté le 29 octobre 2019]

EUROSTAT, 2010. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCadre juridique pour les statistiques européennes, la loi statistique. [en ligne]. 13 juillet 2010. [Consulté le 28 octobre 2019]

EUROSTAT, 2011. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletMémorandum de Wiesbaden. [en ligne]. 28 septembre 2011. DGINS. [Consulté en ligne le 5 novembre 2019]

EUROSTAT, 2015. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletSingle Integrated Metadata Structure v2.0 (SIMS v2.0) and its underlying reporting structures – The ESS Quality and Reference Metadata Reporting Standards – ESMS 2.0 and ESQRS 2.0. [en ligne]. Décembre 2015. Luxembourg. [Consulté le 13 novembre 2019]

EUROSTAT, CSSE, 2017. Ouvrir dans un nouvel ongletCode de bonnes pratiques de la statistique européenne. [en ligne]. 16 novembre 2017. [Consulté le 28 octobre 2019]

KÖRNER, Thomas et WOLFF, Loup, 2016. La fragile comparabilité des durées de travail en France et en Allemagne. In : Insee Analyses. [en ligne]. Juin 2016. N° 26. [Consulté le 29 octobre 2019]

RAO, J. N. K. et MOLINA, Isabel, 2015. Small Area Estimation. Août 2015. Éditions Wiley, Series in Survey Methodology. Seconde édition. ISBN 978-1-118-73578-7

RAZAFINDRANOVONA, Tiaray, 2015. La collecte multimode et le paradigme de l’erreur d’enquête totale. In : Série des documents de travail – Méthodologie statistique – de la Direction de la méthodologie et de la coordination statistique et internationale. [en ligne]. N° M 2015/01. Insee. [Consulté le 29 octobre 2019]

SAUTORY, Olivier, 2018. Méthodes d’estimation sur petits domaines pour l’indicateur AROPE (At-risk of poverty or social exclusion) au niveau régional à partir de l’enquête SRCV. 13e Journées de méthodologie statistique de l’Insee. [en ligne]. 12-14 juin 2018, Paris. [Consulté le 28 octobre 2019]

TASSI, Philippe, 2018. Introduction – Les apports des Big Data. In : Économie et Statistique. [en ligne]. N°505-506, pp. 5-16. [Consulté le 13 novembre 2019]

VINCENEUX, Klara, 2018. Mode de collecte et questionnaire, quels impacts sur les indicateurs européens de l’enquête Emploi ? In : Documents de travail – Insee. [en ligne]. N° F1804. [Consulté le 29 octobre 2019]